Purim Redux: Jew vs. Haman Once Again

This Dvar Torah is written by Rabbi Frederick L Klein, Director, Mishkan Miami: The Jewish Connection to Spiritual Support and Exec. VP, Rabbinical Association of Greater Miami

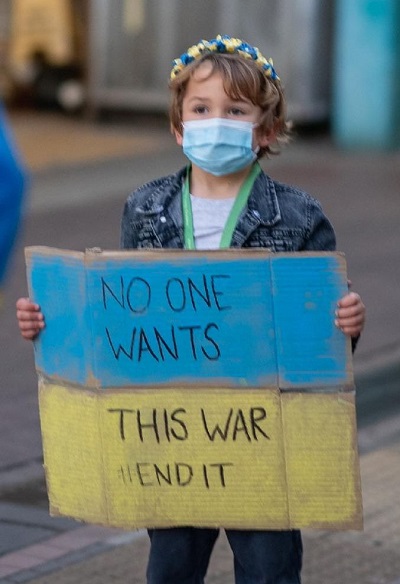

Photo by Egor Lyfar on Unsplash

As I write these words, I have just watched a young 44-year-old former comedian in an olive drab t-shirt address the Congress of the United States and indeed the world. It is a Churchillian moment, although he is speaking in Ukrainian, and this young political novice within weeks has not only become the voice of his people but has embodied the consciousness of the world.

He speaks of a great evil committed upon a powerless people, faces the cameras, and addresses peace-loving people around the world. He asks people whether they will help them fight for values of liberty, human rights, and the basic right to live, or whether the West is all about money and markets.

He asks us whether there are sacred values at all or is the world of international politics just the battle between the powerful and the powerless.

He says all of this at a grave risk to his life and the life of his family, but he must speak out, for that is why he is there in the first place. He has not chosen this, but he nonetheless is compelled.

Oh, did I mention this man, who will go down in history as the moral consciousness of the world, is a Jew?

Purim is a story in which we are introduced to an evil villain, bent on destroying an entire people. While the Torah associates Haman with the tribe of the ancient extinct tribe of Amalekites who attacked the Jewish people unprovoked, the ethos of Amalek sadly is alive and well today. They are not simply alive because the seeds of hatred of the other continue, but that most of the world is silent in light of this hatred.

The key to Haman’s devious plan to kill every man, woman and child was that that the King as well as the people were complicit in his crimes. The plot would have gone nowhere if there was an outcry.

Many have pointed out that God’s name is absent from the book, but perhaps this is the point; the “kingdom’ of Achashverosh is devoid of any of the moral and spiritual values of the real King, the King of Kings.

The prologue of the megillah is a foreshadow of what is to come. The story begins with the story of Vashti who is debased and disgraced in a display of the King’s power, yet nary a word from anyone. Quite the contrary. She is quickly eliminated, and her public banishment (or execution) is advertised throughout the kingdom to instruct wives to know their place. In other words, women need to be subordinated.

It is not a coincidence that the name of the advisor who suggest this misogynistic edict bears the name mehuman, which the rabbis automatically associate with Haman. The rabbis are not simply pointing out the similarity of the names, but the ethos of brute power politics symbolized by this advisor.

Might does make right, and those without power should know their place. Therefore, a Mordechai who does not bow down, must by definition be eliminated. There is a direct line between the domination of women who speak out, and the Jew who fails to bow down.

It is this world of autocratic terror in which Esther finds herself. One might see her as the most powerful woman in the kingdom, but how did she see her own experience?

Here is a woman who is taken against her will into a strange palace, taken from her people and her family, even told not to reveal her true name and identity. She comes from a despised religious and ethnic minority.

She has no royal background like her predecessor Vashti, who the rabbis say was the daughter of Nebuchadnezzar. Likely, she is inexperienced in the art of court politics, negotiation, and unversed in negotiating the power struggles just simmering below the surface. Not everyone would like to see this kingdom succeed. The attempted coup of Bigtan and Teresh was only recently thwarted (end of chapter two).

If anything, she may be more concerned with survival than anything else, and that depends on following protocol, not stepping out of line. She had already seen what happened to her predecessor Vashti, a woman more powerfully connected than she. What real chance would she have?

Thus, while we might think Esther has great power, she may have seen herself as a prisoner in her own home.

These are the real fears that motivate her when Mordechai informs her of Haman’s genocidal plot. Mordechai pleads that she intercede on behalf of the Jewish people. However, far from doing so, she resists, telling Mordechai that she must be summoned before the king, and she has not.

“All the king’s courtiers and the people of the king’s provinces know that if any person, man, or woman, enters the king’s presence in the inner court without having been summoned, there is but one law for him—that he be put to death. Only if the king extends the golden scepter to him may he live” (Esther 4:11).

Of course, this edict is patently absurd and random, but for Esther it seems like the key to survival. Follow what is expected of you. Up to this point, she has been a loyal courtier and queen, and therefore she can do nothing. What does Mordechai expect of her? Is it even fair for Mordechai to ask such a thing? He too knows the etiquette of the palace!

It is at this point Mordechai cannot be silent, and challenges Esther at her core. While Esther may see herself as helpless and without options, Mordechai sees her entire life moving towards this moment. He sees a different Esther.

Mordechai forces her to consider the possibility that it was not just a fluke that she was placed in the position she was. Perhaps the very fact that she has come this far from where she was is proof positive that Esther is more than she really is.

Perhaps she has a natural charisma, a natural magnetism, and that is the reason why she has come so far. Indeed, Mordechai is telling Esther not to see herself as the object of forces beyond herself, but rather the author of her own story, her own mission. She has agency and can make a difference.

At this point, Esther must decide, and calls on all the people to fast and pray for three days. During those three days she looks into the street from the royal palace, and sees the throngs of people praying for her, supporting her.

She is inspired and finds courage she did not know she had. She realized that her life, her journey, has galvanized and inspired the masses. With this encouragement, Esther begins to devise her plan.

On the day she arrives and stands before the king, not only is she not executed, but the king is deeply moved. King Achashverosh sees her and remembers the love he had for her on the day they met, he remembers that she found chen -favor in his eyes.

In a world of political intrigue and suspicion, Esther is the one person who has been true to the King. Upon seeing her, she again ‘finds favor in his eyes’- the same words used when she first became queen!

Even more startingly, unlike Vashti who he debased when he called upon her, he now calls Esther ‘his queen’ and wants to serve her, ‘up to half the kingdom I will give you’ he tells her.

It is at this moment the entire power dynamic of the book changes. Who is the actor and who is the one acted upon? She is a power in her own right- she has a natural grace and has the ear of the king.

In truth, the topsy turvy nature of the Purim story did not come from beyond. There were no Divine ten plagues swooping down from heaven changing the fate of the characters or of history.

Rather the true transformation came from within- first with Mordechai, then with Esther, then with the Jewish people, and then with the entire kingdom. The hidden God had indeed given them all the keys they needed for their own salvation if they only would take it.

Each character and the people at large needed to rise to the occasion, and they did. They found new strength and confidence, and it was this strength and confidence, which provided the key to salvation. Esther was the symbol, becoming the hope all had hoped for.

We are facing a modern-day Haman, even if the victims are not the Jewish people, although the leader is ironically a Jew.

Yet we also are seeing the emergence of a modern-day Esther. In his darkest times, Zelensky might have felt like Esther, and that Ukraine had no hope. Perhaps it was better to simply submit.

Zelensky was not experienced in global politics either, and certainly in navigating what has become a battle with a nuclear power. It seems clear that Putin had gambled that between a dysfunctional, self-absorbed, and inattentive West, and an inexperienced leader, that the prize of Ukraine would not exert such a heavy price. The cries of Ukraine would go unheeded.

Yet, like Esther who gained the attention of the king, Zelensky has risen to the podium, demanding that countries live up to their professed values, and at least for a moment he is winning, even if he is still losing the military battle.

The ninth chapter many people tend to ignore because they find it vengeful and violent. Yet perhaps given the present situation we can rethink the importance of those events.

Many prefer the story to conveniently end with the king hanging the villainous Haman on the gallows, as if that would have solved the problem. In fact, the ethos of Haman outlived his death, and perhaps even transformed him into a martyr for the cause.

Defeating evil is never about defeating one person, but rather destroying the very infrastructure and ideas which make people like Haman possible.

The war at the end of the megillah is a call to arms for the Jewish people and all those who support them to fight. The very fear that the Jewish people experienced, the insecurity of the future, is now experienced by their oppressors, as it should be.

Evil cannot be excused with impunity. While some might see the chapter as one of vengeance, from the standpoint of those who have been terrorized by these violent mobs, it may be justice.

Of course, we would hope for the changing of the heart, and perhaps some did. The megillah says some became Jews (!). However, for those that are suffering right now, perhaps that is a luxury that cannot be afforded.

Neither Persia nor modern day Europe can tolerate tyrannical ideologies that intend to dominate and destroy entire societies.

Purim and the story of the destruction of Amalek tells us that the battle against evil is a long- protracted affair, that the story does not end with the hanging of Haman, or even the end of the war.

The closing verses of the megillah make abundantly clear that the kingdom is still under the control of Achashverosh, hinting that the victory was at best provisional. The kingdom of God, of justice and mercy, is still elusive.

Yet, every generation is called like Mordechai and Esther to speak out. Mordechai and Esther taught that in their days, and Zelensky is teaching this lesson to us today.

Bayamim hahem Bazman Hazeh. May we head the call.

Shabbat Shalom